face2face

Well-Known Member

- Jun 22, 2015

- 8,243

- 1,202

- 113

- Faith

- Christian

- Country

- Australia

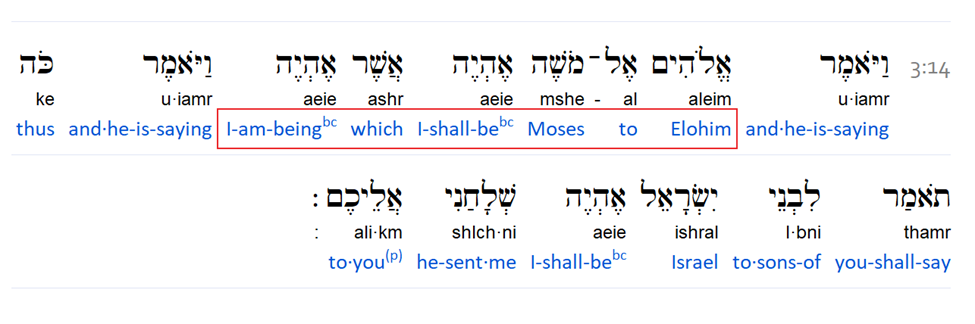

Jesus was the promised Jewish Messiah, but he never claimed to be God or ‘God the Son,’ nor was such an accusation brought against him at his trial. This is significant, especially considering that the Jews had previously attempted to stone him for statements like "Before Abraham was, I am" and "I and the Father are one." Regardless of how the Jewish rulers interpreted these statements, they could not be used as evidence of a claim to deity.

Not only were the Apostles silent on the Trinity, but even those who opposed Jesus had nothing to say about it.

Regarding the few verses in John's Gospel that suggest a profound connection between God and a (assumed) pre-existent Jesus, it must be pointed out that these texts—when understood within the socio-historical context of Second Temple Judaism and 1st Century Christianity—do not provide the Scriptural evidence necessary to radically redefine God as a triune being. John's stated purpose throughout his Gospel is to reveal Jesus' identity, but not in the way that Trinitarianism requires:

• In the first chapter, Jesus is described as "Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph" (v45) and twice called the "Son of God" (v34, v49).

• At the end of John’s Gospel, it is stated: "these are written, that ye might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God" (John 20:31).

The Unitarian understands that John’s Gospel describes a purposeful oneness between God and Jesus, to which disciples can only aspire imperfectly (John 17). It is a significant leap to use these verses to construct a doctrine that God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit are all the same being. “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof; this just isn’t it!”

Bible readers must avoid hasty conclusions based on personifying language in passages such as John 14:16-17. This is simply a useful linguistic device. For the most part—including at Pentecost—the Holy Spirit is described as God’s inanimate power, a view consistent with the portrayal of God’s Spirit in the Old Testament and in pre-Christian writings.

Rabbinic literature and mainstream theologians—even Trinitarian ones—agree that this is the correct lens through which to interpret the New Testament.

Neither in the Gospels, the preaching of the apostles in Acts, the apostolic epistles, nor in the first-century writings of Clement, Polycarp, or the Didache, nor even in most Christian writings up to the 4th century, do we find a clear explanation of God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit as a Trinity.

Instead, we see increasing confusion as Christian philosophy, influenced by pre-Christian Neoplatonic concepts, blurred the identities and natures of God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. This led to a political schism that birthed the Nicene and Athanasian creeds. This strange, convoluted, and often violent path does not reflect the calm theological maturity of the early church, which was guided into all wisdom by the Holy Spirit.

F2F

Not only were the Apostles silent on the Trinity, but even those who opposed Jesus had nothing to say about it.

Regarding the few verses in John's Gospel that suggest a profound connection between God and a (assumed) pre-existent Jesus, it must be pointed out that these texts—when understood within the socio-historical context of Second Temple Judaism and 1st Century Christianity—do not provide the Scriptural evidence necessary to radically redefine God as a triune being. John's stated purpose throughout his Gospel is to reveal Jesus' identity, but not in the way that Trinitarianism requires:

• In the first chapter, Jesus is described as "Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph" (v45) and twice called the "Son of God" (v34, v49).

• At the end of John’s Gospel, it is stated: "these are written, that ye might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God" (John 20:31).

The Unitarian understands that John’s Gospel describes a purposeful oneness between God and Jesus, to which disciples can only aspire imperfectly (John 17). It is a significant leap to use these verses to construct a doctrine that God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit are all the same being. “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof; this just isn’t it!”

Bible readers must avoid hasty conclusions based on personifying language in passages such as John 14:16-17. This is simply a useful linguistic device. For the most part—including at Pentecost—the Holy Spirit is described as God’s inanimate power, a view consistent with the portrayal of God’s Spirit in the Old Testament and in pre-Christian writings.

Rabbinic literature and mainstream theologians—even Trinitarian ones—agree that this is the correct lens through which to interpret the New Testament.

Neither in the Gospels, the preaching of the apostles in Acts, the apostolic epistles, nor in the first-century writings of Clement, Polycarp, or the Didache, nor even in most Christian writings up to the 4th century, do we find a clear explanation of God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit as a Trinity.

Instead, we see increasing confusion as Christian philosophy, influenced by pre-Christian Neoplatonic concepts, blurred the identities and natures of God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. This led to a political schism that birthed the Nicene and Athanasian creeds. This strange, convoluted, and often violent path does not reflect the calm theological maturity of the early church, which was guided into all wisdom by the Holy Spirit.

F2F