Bs"d

"Echad" means one.

Echad ENG

3. Did non-Christian Jewry have their OWN "problem" of 'plurality in the Godhead' and/or with a supra-human messiah?

Absolutely!

I have cited the specific passages, and discussed elsewhere the "plurality tensions" within the Tanakh/OT, within the Pseudepigrapha, and within Rabbinic Judaism.

What I would like to do here is simply to offer a few summary statements by scholars on two points: (1) the supra-human expectation of SOME strands of messianic hope; and (2) the continuity between

pre-Nicene Christian "plural-tarianism" and the Jewish milieu of the 1st century.

First, let me offer two quotes on the 'deity' of the messianic figure (emphases mine):

The first is from Jacob Neusner, famed scholar of rabbinics ["Mishnah and Messiah", JTM:275]:

"We focus upon how the system laid out in the Mishnah takes up and disposes of those critical issues of teleology worked out through messianic eschatology in other, earlier versions of Judaism. These earlier systems resorted to the myth of the Messiah as savior and redeemer of Israel, a supernatural figure engaged in political-historical tasks as king of the Jews, even a God-man facing the crucial historical questions of Israel's life and resolving them: the Christ as king of the world, of the ages, of death itself."

And the second is from Qumran scholar John Collins [SS:168-169]:

"The notion of a messiah who was in some sense divine had its roots in Judaism, in the interpretation of such passages as Psalm 2 and Daniel 7 in an apocalyptic context. This is not to deny the great difference between a text like 4Q246 and the later Christian understanding of the divinity of Christ. But the notion that the messiah was Son of God in a special sense was rooted in Judaism, and so there was continuity between Judaism and Christianity in this respect, even though Christian belief eventually diverged quite radically from its Jewish sources."

Secondly, I want to offer this extended quote from Ellis, who gives more detail on this 'continuity' [OTEC:112-116]:

"The New Testament writers' conception of corporate personality [for example, King:Nation, Tribe

erson, Messiah:Remnant] extends to an understanding of God himself as a corporate being, a viewpoint which underlies their conviction that Jesus the Messiah has a unique unity with God and which later comes into definitive formulation in the doctrine of the Trinity. The origin of this conviction, which in some measure goes back to the earthly ministry of Jesus, is complex, disputed and not easy to assess. One can here only briefly survey the way in which the early Christian understanding and use of their Bible may have reflected or contributed to this perspective on the relationship of the being of God to the person of the Messiah.

"Already in the Old Testament and in pre-Christian Judaism the one God was understood to have 'plural' manifestations. In ancient Israel he was (in some sense) identified with and (in some sense) distinct from his Spirit or his Angel. Apparently, Yahweh was believed to have 'an indefinable extension of the personality,' by which he was present 'in person' in his agents. Even the king as the Lord's anointed (= 'messiah') represented 'a potent extension of the divine personality.'

"In later strata of the Old Testament and in intertestamental Judaism certain attributes of God - such as his Word or his Wisdom- were viewed and used in a similar manner. In some instances the usage is only a poetic personification, a description of God's action under the name of the particular divine attribute that he employs. In others, however, it appears to represent a divine hypostasis, the essence of God's own being that is at the same time distinguishable from God.

"From this background, together with a messianic hope that included the expectation that Yahweh himself would come to deliver Israel, the followers of Jesus would have been prepared, wholly within a Jewish monotheistic and 'salvation history' perspective, to see in the Messiah a manifestation of God. In the event, they were brought to this conclusion by their experience of Jesus' works and teachings, particularly as it came to a culmination in his resurrection appearances and commands. Although during his earthly ministry they had, according to the Gospel accounts, occasionally been made aware of a strange otherness about Jesus, only after his resurrection do they identify him as God. Paul, the first literary witness to do this, probably expresses a conviction initially formed at his Damascus Christophany. John the Evangelist, who wrote later but who saw the risen Lord (and was a bearer of early traditions about that event), also describes the confession of Jesus as God as a reaction to the resurrection appearances. Yet, such direct assertions of Jesus' deity are exceptional in the New Testament and could hardly have been sustained among Jewish believers apart from a perspective on the Old Testament that affirmed and/or confirmed a manifestation of Yahweh in and as Messiah.

"The New Testament writers usually set forth Messiah's unity with God by identifying him with God's Son or Spirit or image or wisdom or by applying to him biblical passages that in their original context referred to Yahweh. They often do this within an implicit or explicit commentary (midrash) on Scripture and thereby reveal their conviction that the 'supernatural' dimension of Jesus' person is not merely that of an angelic messenger but is the being of God himself.

"The use of Scripture in first and second century Judaism, then, marked a watershed in the biblical doctrine of God. At that time it channeled the imprecise monotheism of the Old Testament and early Judaism in two irreversible directions. On the one hand Jewish-Christian apostles and prophets, via 'corporate personality' conceptions and Christological exposition, set a course that led to the trinitarian monotheism of late Christianity.

On the other hand the rabbinic writers, with their exegetical emphasis on God's unity, brought into final definition the unitarian monotheism of talmudic Judaism."

And then from volume two in Michael Brown's excellent trilogy, Answering Jesus Objections to Jesus, p7f:

"Maybe the problem lies with an overemphasis on the often misunderstood--and frequently poorly explained--term Trinity. Perhaps it would help if, for just one moment, we stopped thinking about what Christians believe--since not everything labeled "Christian" is truly Christian or biblical--and pictured instead an old Jewish rabbi unfolding the mysteries of God. Listen to him as he strokes his long, gray beard and says, "I don't talk to everyone about this. These things are really quite deep. But you seem sincere, so I'll open up some mystical concepts to you."

"And so he begins to tell you about the ten Sefirot, the so-called divine emanations that act as "intermediaries or graded links between the completely spiritual and unknowable Creator and the material sub-lunar world." When you say, "But doesn't that contradict our belief in the unity of God?" he replies,

"God is an organic whole but with different manifestations of power-just as the life of the soul is one, though manifested variously in the eyes, hands, and other limbs. God and his Sefirot are just like a man and his body: His limbs are many but He is one. Or, to put it another way, think of a tree which has a central trunk and yet many branches. There is unity and there is multiplicity in the tree, in the human body, and in God too. Do you understand?"

"Now think of this same rabbi saying to you, "Consider that in our Scriptures, God was pictured as enthroned in heaven, yet at the same time he manifested himself in the cloud and the fire over the Tabernacle while also putting his Spirit on his prophets. And all the while the Bible tells us that his glory was filling the universe! Do you see that God's unity is complex?"

"And what if this rabbi began to touch on other mystical concepts of God such as "the mystery of the three" (Aramaic, raza'di-telatha), explaining that in the Zohar there are five different expressions relating to various aspects of the threefold nature of the Lord? What would you make of the references to "three heads, three spirits, three forms of revelation, three names, and three shades of interpretation" that relate to the divine nature? The Zohar even asks, "How can these three be one? Are they one only because we call them one? How they are one we can know only by the urging of the Holy Spirit and then even with closed eyes."" These issues of "the Godhead" are deep!

My point should be obvious: Even in the major controversial issues such as the deity of the messiah and the plurality within God, the Christians were still not radically out of synch with the Judaism of the day! (We will see later where the uniqueness came from, but it was NOT from the theological backdrop, to be sure).

You sit with a problem-you recanted the true Messiah who is YHVH.

Second, from the TWOT:

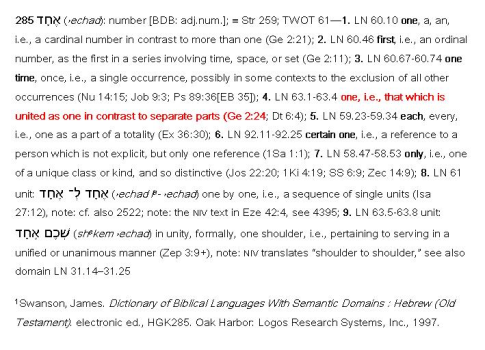

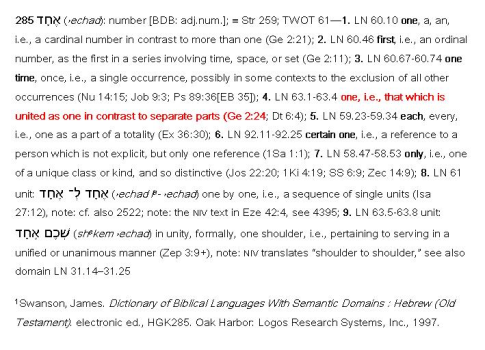

'Echad one, same, single, first, each, once,.

This word occurs 960 times as a noun, adjective, or adverb, as a cardinal or ordinal number, often used in a distributive sense. It is closely identified with yahid “to be united” and with rosh “first, head,” especially in connection with the “first day” of the month (Gen 8:13).

It stresses unity while recognizing diversity within that oneness.

--and stop "blaming the Christians" for [altering] your Torah-we had nothing to do with it.

You have a problem.